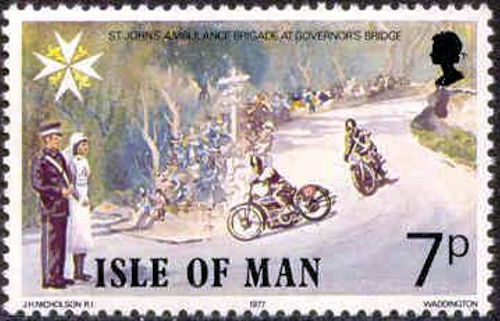

Continental Circus - part 2: After WW IIThe outbreak of World War II brought the Continental Circus to a standstill, but in the early 1950s it was resumed. It were mainly the British and Commonwealth private drivers who were part of the Continental Circus. In these years accidents, fatal or otherwise, were lurking. Most circuits were downright deadly by today's standards, and ambulances and emergency services often had to be called into action several times. |

|

|

This was in stark contrast to the GP organisations, which assumed that one had to drive to become world champion, and therefore did not consider good remuneration necessary.

Riders were not only responsible for maintaining their machines themselves, but also had to provide their own transport as drivers. Often, their partners also had to step in as pit crew, attendants and assistant drivers.

The transport itself was no easy task either. Machines had to have a carnet, and they had to be cleared in and out at every border. Some countries also required visas to be allowed into the country, which often caused long delays. It often required a lot of patience and tact from the drivers and escorts. Sometimes a visa was only granted if an invitation from the race organizer could be presented. In a time without mobile phones and email, this administrative hassle certainly made it no easy task to arrange everything on paper.

Ex-army three-tonners were often used for transport. Advantage was that these also offered room to sleep, but their disadvantage was that they had a very low cruising speed. So this also meant long travelling times to get from one circuit to another.

Besides all the arranging, driving was the easiest part of a racing driver's life in those days. The circuits varied enormously in layout and length. There were the GP circuits of Assen, Francorchamps, Hockenheim, Nürburgring and Bremgarten, but also circuits that were formed by closing off public roads, such as Floreffe, Mettet, Gedinne, St. Wendel, Salzburg, Hedemora, and so on.

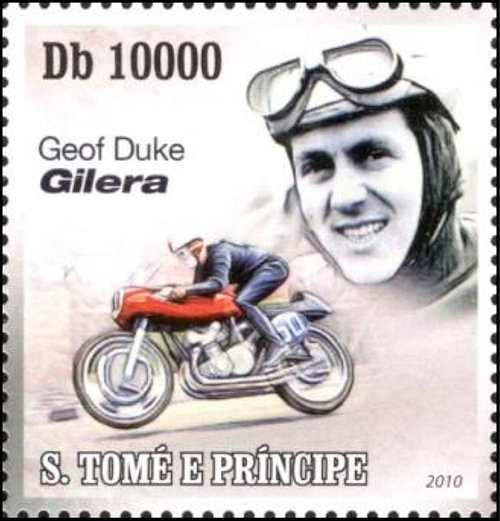

In the early 1950s, the races at Mettet and Floreffe in April were often used as tests for the upcoming season. Big names who won there included Les Graham, Reg Armstrong, Geoff Duke and Bill Lomas.

However, they were not the safest tracks, with long straights and treacherous bends through villages and forests. Therefore racing was banned at Floreffe in 1956 after Fergus Anderson died there.

Mettet and other tracks such as Tubbergen, Chimay, Gedinne, Zandvoort, Schotten and Solitude would continue to hold motorcycle races until the 1970s.

To be continued

Hans Baartman